Landscaping Games [EN]

![Landscaping Games [EN]](/content/images/size/w960/2025/11/Kavarna.jpg)

This paper sketches out the concept of "landscaping games" with the help of research in cultural techniques. Those are also practices of spatialization, challenging the prevailing assumption that gaming landscapes refer exclusively to virtual environments. By opening with the historical example of coffee houses as designed gaming spaces, the analysis demonstrates that spatial design for play predates digital media and continues to inform contemporary game design practices. The paper argues that games function not merely as representations of space but as active cultural techniques that shape spatial understanding through fundamental operations of movement, collection, and navigation.

Through detailed examination of key case studies—Minecraft's negative spatialization mechanics, the roguelike topology of Hoplite, and the cinematic modularization pioneered by Prince of Persia and extended in Assassin's Creed—the paper traces how games transform environments into possibility spaces for action. Drawing on Espen Aarseth's concepts of ludoforming and de-ludification, the analysis reveals the systematic processes by which topographical landscapes are converted into ludic topologies through compression, adaptation, and strategic spatial organization.

The theoretical framework integrates Bernhard Siegert's concept of cultural techniques with Johan Huizinga's foundational insight that "culture originates in play," arguing that basic gameplay operations constitute pre-verbal spatial practices that precede abstract conceptualizations of space. The paper demonstrates that whether crudely-styled or cinematically polished, all gaming landscapes are primarily "landscaped games" shaped fundamentally by the demands of play rather than representational fidelity.

This approach repositions game studies to focus on operative and technical dimensions of spatial production rather than narrative or representational aspects, offering new insights into how games participate in broader cultural processes of spatial imagination and environmental understanding.

Into to the Kavarna

I consider myself to be an expert for a very specific gaming landscape: the coffee house. You might think of that being far fetched, but coffee houses used to be spaces for playing games. As we can see in a Novis Orbis Pictus the encyclopedic entry of Kavarna - Kaffeehaus is compared to other gastronomic spaces full of gameplay action. Whether it was billiards, chess, card games or simply participating in public discourse. These were places designed for gaming.[1]

Nowadays, and also if you look at the call for this conference, it almost goes without saying that when we talk about gaming landscapes / environmental storytelling we usually mean virtual environments. That's why I open with this little detour: to question that very assumption.

If the landscape is a fundamental notion to describe games, it should be applicable to every game. Then it's the chequered board, the level green felt table with its holes and the newspapers on display. Zooming out, one can see like in a theme park or arcade hall the different games at display. In case of classical games it's difficult to point at a particular design intention, that shaped the landscape of any particular game, like e.g. backgammon. But we can see the host of the coffee house as someone who is designing a room that caters to the needs of players (Manzo, 2014; Oldenburg, 1989). So let's say the coffee shop owner landscapes his facilities into a gaming environment — So, what could be then a landscaping game?

The „landscaping game” par excellence

Clearly the most popular title from the sandbox genre is Minecraft. What you do there is, quite literally, craft mines. You dig, you tunnel, you collect resources, and then you combine and use them to build structures on the surface. Each round offers you a randomly generated world to be landscaped (Worsley & Bar-El, 2020).

The survival mode — so you could oppose this argument — adds restrictions, obstacles and rules to the free form play with the block surroundings: but this enforces cleverly the core logic of the game, which is based on a negative conception of space. Landscaping takes place literally by carving out voids in the ground. You extract resources from below, which you can then recombine and use to positively shape the surface world.

And here's the interesting twist: the underground is not the dangerous place – the surface is. It's upside down. Normally, tunnels, sewers, mines and dungeons are the dark, perilous spaces, crowded with monsters and traps. But in Minecraft, that's shifted: the surface, populated with zombies and other threats, is what you fear at night. Then the underground becomes your refuge.

This inversion of the mystical return to the cave as a default setting is itself almost dystopian or apocalyptic. (Think of popular titles like Fallout or films like 12 Monkeys – humans escaping into underground shelters.) And it's the opposite of the classic dungeon crawl, where you normally leave town into hostile dungeons. That's why one can call structurally the tunneling of Minecraft as a game of negative landscaping: the equipment and type of blocks determine how fast the avatar moves through solid ground, creating homogeneous space, that can be freely navigated.

Aarseth's concept of ludoforming

In contrast to this concept of 'landscaping' as a game, Espen Aarseth already coined the term ludoforming, but to describe a game design practice — not the induced play: real-world or fictional topographies are turned into playable spaces (Aarseth, 2019): Middle Earth in Lord of the Rings games, the American West in Red Dead Redemption, or historical epochs in Assassin's Creed, contaminated area of Chernobyl in S.T.A.L.K.E.R.

Aarseth observes that this process is never smooth: There are always compressions, adaptations, invisible walls, shortcuts – maps are cut up and rearranged so they fit the gameplay. He distinguishes in the course of his article between simulation, adaptation, theming, remediation. A complicated taxonomy for what is, in essence, the simple process of turning a topographical landscape into a ludic topology, that can be navigated within the scheme, a game has to offer.

But there's also the reverse: he mentions spaces inside games that are de-ludified: taverns, cities, social hubs where the grinding of the dungeon is paused, where you trade, chat, or simply hang out (Aarseth, 2019). Or think of Fortnite Holocaust museums (https://www.stiftung-digitale-spielekultur.de/spiele-erinnerungskultur/fortnite-holocaust-museum-voices-of-the-forgotten/, accessed 3.11.2025), where players just present things without engaging in combat. If you visit GTA's Vice City without playing the missions, it's basically tourism in a fictional place.

So, ludoforming and de-ludification show how game designers translate any given topography into playable space, while players might find usage beyond the intentional ludic purpose. But what about games that have almost no de-ludified niches? Where everything is reduced to a strictly ludic concept?

The rogue-like topology

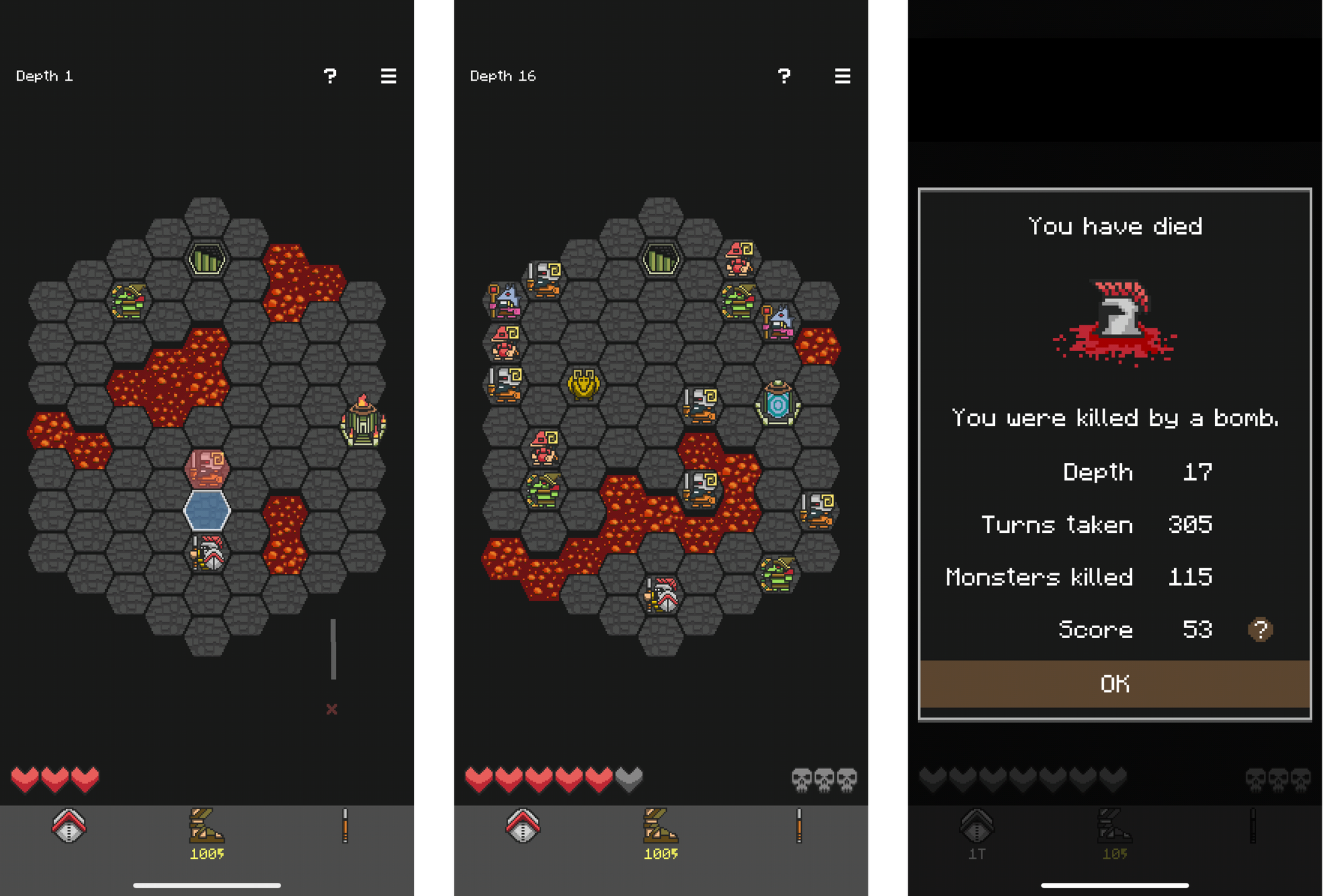

Hoplite is a small game from 2013, originally created during a game jam. It's a classic roguelike. Each level is a hexagonal dungeon filled with enemies called "depth". You descend deeper, you fight, you survive – or you die trying, i.e. losing all the achievements of that run. This is called "Permadeath" in the gamer lingo: No safe spaces, no city breaks, no taverns. Just the dungeon and at some point a push your luck mechanism: players are confronted with the decision whether to descend further, in chase of a higher score, or leaving the dungeon through a portal.

Rogue from 1980 had limited capacities, so games economized: even though infinite dungeons were procedurally generated, no room was left for social spaces and personal customization, just black voids filled anew with each session. No space for fluff, lore or detailed graphics — only ASCII code. Hoplite keeps this spirit.

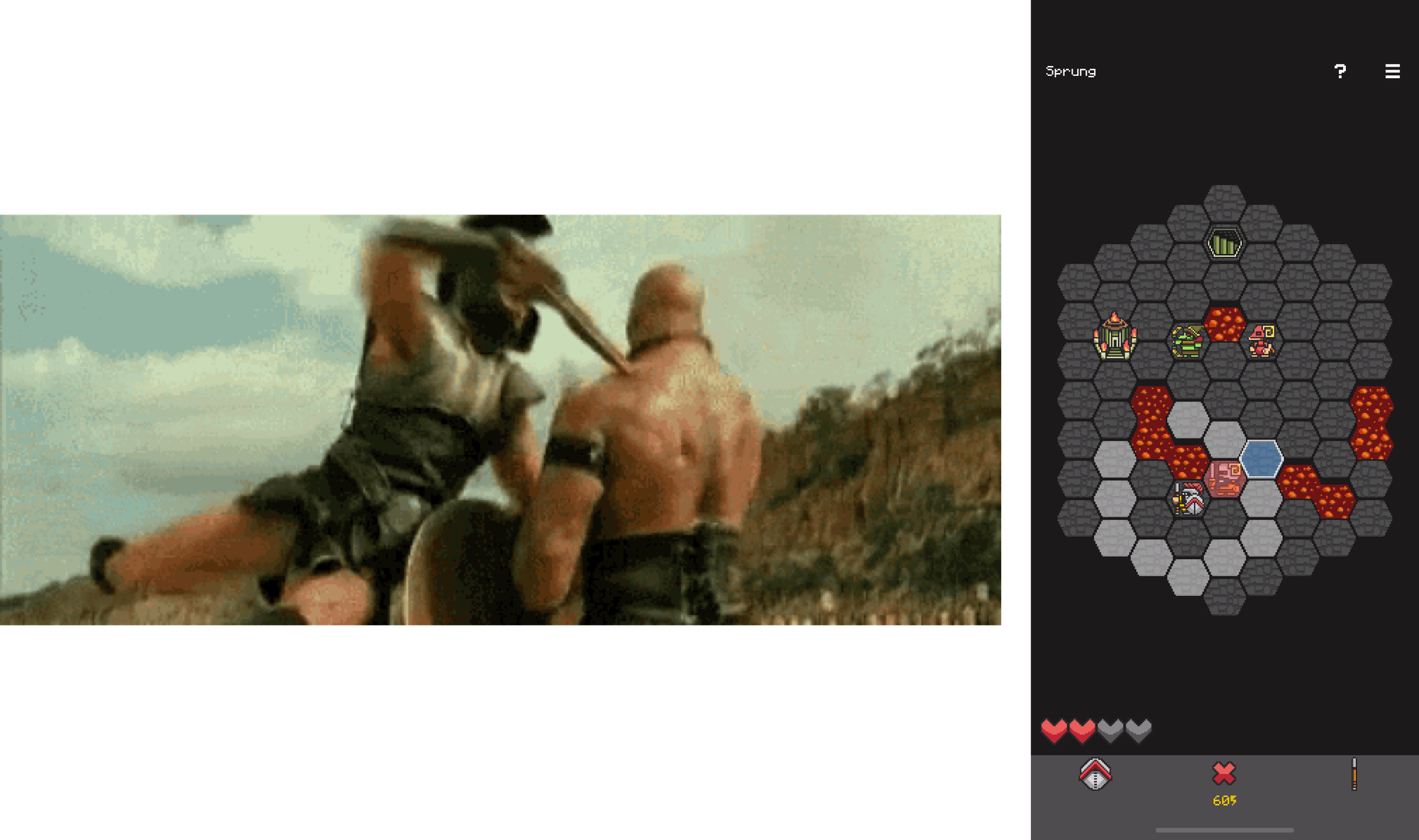

But Hoplite also adds a very thin thematic layer strengthening the very slim design, that even in the elaborated version caters to a typical retro-taste. Your avatar represents a hoplite, a classical Greek fighter. You can pray to Greek deities, equipped with spear, sword, shields, and sandals – all of it resonates with pop-cultural imagery. The early 2000s with several popular feature films like Wolfgang Peterson's Troy or Zack Snyder's 300 serve as visual repository. Their stylized choreography of stabbing, while leaping over enemies, punching, and kicking is clearly referenced in the mechanics of Hoplite.

Throwing your spear, jumping over enemies, outmaneuvering them – these are abstract hexagonal moves, but they evoke cinematic images the audience has already internalized. So, Hoplite offers tactical gameplay, which is rather abstract and lets you strategise over whether to move simply one tile, or use energy to jump over a field. But the theme helps you understand these moves easier, as you can recall the meaning of your options within the cinematic choreographies of combat. So the game system remediates cultural memory — still thematically, but within the ludic scheme, which would look quite different, if this weren't a Greek fighter from the early 2010s. The ludic mechanics themselves are infused with a specific historical imagination.

Cinematic modularization of space

The original Prince of Persia (1989) had pioneered this way of cinematic remediation. In early iterations, Jordan Mechner actually designed it with a level editor – modular tiles used to build the levels. The game world was literally a puzzle of prefabricated spatial units. Later, for cinematic reasons, the scope was reduced: fewer levels, but tightly choreographed, almost like a film.

Prince of Persia then became a milestone in cinematic gameplay. The rotoscoped animation gave the avatar a lifelike quality, and the time-limited adventure turned the modular dungeon into a dramatic stage.

And from there, we can trace a genealogy directly into one of Ubisoft's biggest brands. Patrice Désilets, who worked on Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, went on to create Assassin's Creed. Again, a white-cloaked avatar, moving through choreographed environments, heavily indebted to contemporary cinema like Kingdom of Heaven.

Assassin's Creed also adds a new layer: pseudo-archaeology. It sells itself as historical reconstruction, even while cutting, compressing, and adapting space for gameplay (Huber, 2014). This became particularly visible after the Notre-Dame fire in 2019. Some speculated whether Ubisoft's 3D models of the cathedral could aid reconstruction. Ubisoft even offered support and donated money. Quickly it was clarified: the game models are artistic approximations, not precise enough for restoration. They were built for playability, not for architectural accuracy. Nonetheless a body that scans his environments for possibilities to climb on and jump over is a ludification against design intentions — what was called within virtual game spaces de-ludification.

So instead of saying the architectural structure was ludoformed (together with the necessary compromises), when copied into its digital form, I'd rather say the bodily games of climbers and parkour is remediated within a third person action adventure set in 18th century Paris.

The invention of cutscenes, which plays a crucial role in this cinematic modularization, represents a specific technique of spatial and temporal organization that bridges gameplay and narrative representation (Huber, 2014).

Cultural techniques of spatialization in Game contexts

Whether it's crudely-styled Minecraft, retro-pixels Hoplite or fancy titles from Prince of Persia to Assassin's Creed with cinematic polish – all gaming landscapes are shaped by the demands of play. They are landscaped games in the first place. Even when they reference history, mythology, or architecture, they bend historical representations to produce ludic purposes.

Here, the concept of cultural techniques (Siegert, 2015) helps grasping the object conceptually: Cultural techniques are older than the abstract concepts that originate from them: most basic operations – counting days comes before a notion of time, drawing lines in the ground, opening/closing doors make up what space is before we can philosophically engage with such abstract matters. So we're continuously processing the real pre-verbally. Research in cultural techniques allow to spell out how "culture originates in play", as Huizinga proclaimed (Huizinga, 1938). Like time and space, also games are spontaneously played and then turned into games, which ossify and become conventional culture.

In games, the basic gameplay operations are movement, collection, navigation (Lammes, 2008). They are evident before we can talk about a formalized game. In the research project Ludological Investigations (ludology.uni-ak.ac.at), we are collecting such cultural techniques of play, that coupled together commodify game spaces. But in general it's the series of decisions that makes the player a gamer.

When digging tunnels in Minecraft, when leaping tiles in Prince of Persia, when climbing Notre-Dame in Assassin's Creed – the player doesn't need to pay attention to the presented narrative. Users of gaming software are simply enacting the spatial practices that were worked into the gaming systems. Games landscape environments by turning them into possibility spaces for action.

Environmental storytelling is in this model merely the implementation of decision-critical combination of datasets into refashioned interfaces that become visually more and more coherent, which is at the same time considered to be more compelling. From the text-based Colossal Cave Adventure over SCUMM-point and click to Detroit: Become Human and ultimately Bandersnatch a Black Mirror-Episode that one is actually playing in hers or his Netflix account.

As Aarseth says, ludoforming is a form of ludification, a more general term to describe the process of "turning things into games". At this point he is not aiming at a sufficient definition of the purification process, but simply wants to demarcate the border to gamification (Deterding et al., 2011). There (in Aarseth’s scheme) game elements are slapped onto other worldly systems, while ludification creates those artificial conflicts but from the cultural techniques that enact the players' choices.

Games always operate through ludification. In the words elaborated here: Games spatialize, they cultivate, they landscape in regard to the bodies, who navigate those spaces and player collectives that inhabit them. And that makes them powerful cultural artifacts for understanding how we, as players, construct meaning in space.

Originally this starts with the design of playful textbooks, such as Comenius' Orbis sensualium pictus (1658). This first pictorial encyclopedia already demonstrates how spatial organization and visual arrangement turn the act of paging through a book into a set of cultural techniques that shape learning and understanding through play-like navigation (Huber, 2024). The virtualization of space in such educational contexts prefigures not only newer issues of pictorial encyclopedias but many of the very elemental, spatial techniques we observe in contemporary digital games. So we’re back at the start, but can see now the layout of the double page as a landscape, that we are cruising with our pair of eyes.

Notes

[1] Of course the colonial history of coffee consumption and its connection to the enlightenment is a rich and interesting topic for further research, but for the conceptual work here this superficial account of all this play happening in this designated area suffices (Cf. Aljunied, 2014; Graeber & Wengrow, 2021)

References

- Aarseth, E. (2019). Ludoforming: The design strategies of Assassin's Creed. In The Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies (pp. 297-304). Routledge.

- Aljunied, K. (2014). Coffee-shops in Colonial Singapore: Domains of contentious publics. History Workshop Journal, 77(1), 65-85.

- Barthes, R. (2017). Das Reich der Zeichen (20th ed., M. Bischoff, Trans.). Suhrkamp. (Original work published 1970)

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining "gamification". In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference (pp. 9-15). ACM.

- Graeber, D. (2015). The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy. Melville House Publishing.

- Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. (2021). The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Huber, S. (2014). The remediation of history in Assassin's Creed. In T. Winnerling & F. Kerschbaumer (Eds.), Early Modernity and Video Games. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Huber, S. (2014). Zur Geschichte der Cutscenes. In T. Winnerling & F. Kerschbaumer (Eds.), Frühe Neuzeit in Computerspielen. Transcript.

- Huber, S. (2024). "wann er also das ganze Buch durchlauffen". Über die Virtualität des Raumes im Orbis sensualium pictus (1658). In C. Gundermann, B. Hanke, & M. Schlutow (Eds.), Digital Public History: analytische Zugänge und Lernpotenziale digitaler Geschichte (Geschichtsdidaktik diskursiv - Public History und Historisches Denken, Band 12). Peter Lang.

- Huizinga, J. (1938). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture. Beacon Press.

- Lammes, S. (2008). Spatial regimes of the digital playground: Cultural functions of spatial practices in computer games. Space and Culture, 11(3), 260-272.

- Manzo, J. F. (2014). Machines, people, and social interaction in "third-wave" coffeehouses. Journal of Arts and Humanities, 3(8), 1-12.

- Oldenburg, R. (1989). The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community. Paragon House.

- Siegert, B. (2015). Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real. Fordham University Press.

- Worsley, M., & Bar-El, D. (2020). Spatial reasoning in Minecraft: An exploratory study of in-game spatial practices. In Proceedings of the International Conference of the Learning Sciences (pp. 709-716). International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Ludography

- Assassin's Creed (2007). [Video game]. Ubisoft Montreal. Ubisoft.

- Bandersnatch (2018). [Interactive film]. House of Tomorrow, Netflix.

- Colossal Cave Adventure (1976). [Video game]. Will Crowther.

- Detroit: Become Human (2018). [Video game]. Quantic Dream. Sony Interactive Entertainment.

- Fallout (1997). [Video game]. Interplay Productions. Interplay Entertainment.

- Fortnite (2017). [Video game]. Epic Games.

- Grand Theft Auto: Vice City (2002). [Video game]. Rockstar North. Rockstar Games.

- Hoplite (2013). [Video game]. Douglas Cowley (Magma Fortress).

- The Lord of the Rings (various titles, 2002–present). [Video game series]. Various developers. Various publishers.

- Minecraft (2011). [Video game]. Mojang Studios. Microsoft.

- Prince of Persia (1989). [Video game]. Jordan Mechner. Brøderbund.

- Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (2003). [Video game]. Ubisoft Montreal. Ubisoft.

- Red Dead Redemption (2010). [Video game]. Rockstar San Diego. Rockstar Games.

- Rogue (1980). [Video game]. Michael Toy, Glenn Wichman, Ken Arnold.

- S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl (2007). [Video game]. GSC Game World. THQ.

Filmography

- Gilliam, T. (Director). (1995). 12 Monkeys [Film]. Atlas Entertainment, Classico, Universal Pictures.

- Petersen, W. (Director). (2004). Troy [Film]. Warner Bros. Pictures, Plan B Entertainment, Radiant Productions.

- Scott, R. (Director). (2005). Kingdom of Heaven [Film]. 20th Century Fox, Scott Free Productions.

- Snyder, Z. (Director). (2006). 300 [Film]. Warner Bros. Pictures, Legendary Pictures, Virtual Studios.

Member discussion